Christina Thatcher, Cardiff Metropolitan University

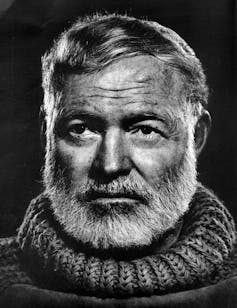

Ernest Hemingway famously said that writers should “write hard and clear about what hurts”. Although Hemingway may not have known it at the time, research has now shown that writing about “what hurts” can help improve our mental health.

There are more than 200 studies that show the positive effect of writing on mental health. But while the psychological benefits are consistent for many people, researchers don’t completely agree on why or how writing helps.

One theory suggests that bottling up emotions can lead to psychological distress. It stands to reason, then, that writing might increase mental health because it offers a safe, confidential and free way to disclose emotions that were previously bottled up.

However, recent studies have begun to show how an increase in self-awareness, rather than simply disclosing emotions, could be the key to these improvements in mental health.

In essence, self-awareness is being able to turn your attention inward towards the self. By turning our attention inward, we can become more aware of our traits, behaviour, feelings, beliefs, values and motivations.

Research suggests that becoming more self-aware can be beneficial in a variety of ways. It can increase our confidence and encourage us to be more accepting of others. It can lead to higher job satisfaction and push us to become more effective leaders. It can also help us to exercise more self-control and make better decisions aligned with our long-term goals.

Self-awareness is a spectrum and, with practice, we can all improve. Writing might be particularly helpful in increasing self-awareness because it can be practised daily. Rereading our writing can also give us a deeper insight into our thoughts, feelings, behaviour and beliefs.

Here are three types of writing which can improve your self-awareness and, in turn, your mental health:

Expressive writing

Expressive writing is often used in therapeutic settings where people are asked to write about their thoughts and feelings related to a stressful life event. This type of writing aims to help emotionally process something difficult.

Research shows that expressive writing can enhance self-awareness, ultimately decreasing depressive symptoms, anxious thoughts and perceived stress.

Reflective writing

Reflective writing is regularly used in professional settings, often as a way to help nurses, doctors, teachers, psychologists and social workers become more effective at their jobs. Reflective writing aims to give people a way to assess their beliefs and actions explicitly for learning and development.

Writing reflectively requires a person to ask themselves questions and continuously be open, curious and analytical. It can increase self-awareness by helping people learn from their experiences and interactions. This can improve professional and personal relationships as well as work performance, which are key indicators of good mental health.

Creative writing

Poems, short stories, novellas and novels are all considered forms of creative writing. Usually, creative writing employs the imagination as well as, or instead of, memory, and uses literary devices like imagery and metaphor to convey meaning.

Writing creatively offers a unique way to explore thoughts, feelings, ideas and beliefs. For instance, you could write a science fiction novel that represents your concerns about climate change or a children’s story that speaks to your beliefs about friendship. You could even write a poem from the perspective of an owl as a way to represent your insomnia.

Writing creatively about challenging experiences, like grief, can also offer a way to communicate to others something which you feel is too complicated or difficult to say directly.

Creative writing encourages people to choose their words, metaphors and images in a way that really captures what they’re trying to convey. This creative decision-making can lead to increased self-awareness and self-esteem as well as improved mental health.

Writing for self-awareness

Self-awareness is a key component for good mental health and writing is a great place to start.

Why not take some time to write down your feelings about a particularly stressful event that has happened during the pandemic? Or reflect on a difficult work situation from the last year and consider what you have learned from it?

If you prefer to do something more creative, then try responding to this prompt by writing a poem or story:

Think about the ways your home reveals the moment we are currently in. Is your pantry packed with flour? Do you have new objects or pets in your home to stave off loneliness or boredom? What you can see from your window that reveals something about this historic moment?

Each of these writing prompts will give you a chance to reflect on this past year, ask yourself important questions, and make creative choices. Spending just 15 minutes doing this may give you an opportunity to become more self-aware – which could lead to improvements in your mental health.

Christina Thatcher, Creative Writing Lecturer, Cardiff Metropolitan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

But in the same way that stories multiplied and diversified across the world, so did the forms and meanings of gift-giving.

But in the same way that stories multiplied and diversified across the world, so did the forms and meanings of gift-giving. Exchanging gifts appears to be a universal human practice but cultural awareness is advisable. Social occasions for gift-exchange occur throughout the year in China, but in a culture where maintaining ‘face’ ranks highly, what to give, to whom, when, and exactly how much to put into the ‘little red envelope’ poses an etiquette quagmire to the unwary.

Exchanging gifts appears to be a universal human practice but cultural awareness is advisable. Social occasions for gift-exchange occur throughout the year in China, but in a culture where maintaining ‘face’ ranks highly, what to give, to whom, when, and exactly how much to put into the ‘little red envelope’ poses an etiquette quagmire to the unwary.